Explore interactive map of Lincoln, NE

View full sized bird's eye view map

Contents

Introduction to Lincoln, NE: A Gilded Age Plains City

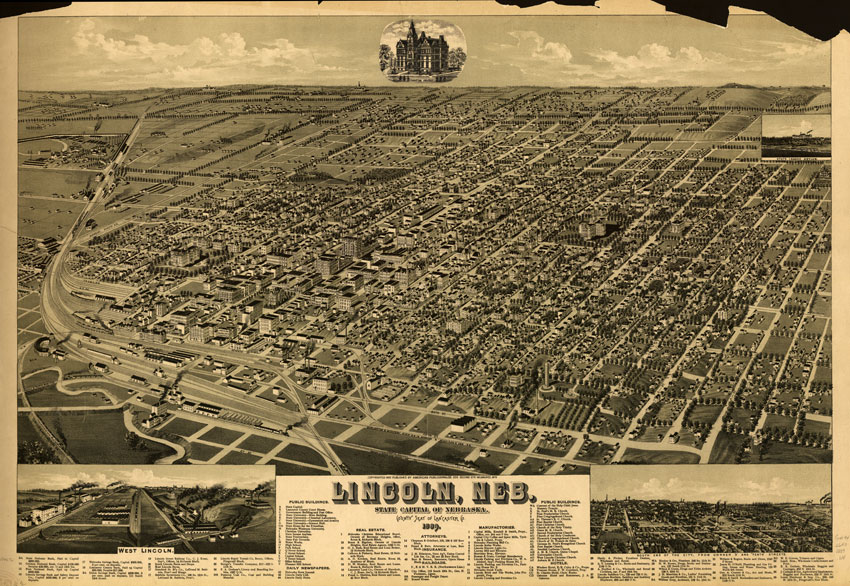

Welcome to Lincoln, Nebraska in 1889. The well known panoramic map, or "birds-eye view," of Lincoln, seen here, signified a moment of pride and accomplishment for contemporary residents. Within two decades, their city had developed an urban landscape with the complexity and diversity that no individual could encompass from any one single viewpoint, although many tried. Lincolnites quickly developed a favorite pastime of capturing different slices of their city by spying from the tallest buildings: the state capitol, the top of University Hall's tower, and the Burr Block. The new Lincoln Hotel, after its 1890 grand opening, became another popular vantage point with its own panoramic view of Government Square. (Figure 1) (Figure 2) (Figure 3) (Figure 4)

One such attempt to view the city as a whole was made by Thomas Hyde, a resident in 1888. Hyde observed the city from atop a five story building located in the heart of the city (Ninth and O streets) and wrote that he seemed hardly above the "living picture of urban life." From that lofty "outlook" — well below that of the birds-eye view of the panoramic map reference — he saw an "unabating tide of life miles in extent with all the varied shades of fashion." Hyde went on to describe O Street as "the main channel, with its buildings, commercial hives, and ragged skyline, (that) seem like a gulch of life in a canyon of masonry. . . .The swelling, hurrying flood of animation, mingling with a world of commerce on wheels, crowded street cars, omnibuses, coaches and cabs, moves on." Additionally, he was captured by the "human throng" where "youth jostles age, poverty on foot stares Croesus in his carriage. . . . At night hundreds of lights twinkle until in the distance they resemble a ribbon of fire and the crowd flows between the lines of flame. . . diminishing as the hours wane." While Hyde's roof-top description and the panoramic view make the city seem unified, prosperous, and proud, the documents collected here indicate that "on the ground" Lincoln, was in fact like so many other cities of the time: a site of conflict, a contested terrain, and, to some, a battlefield of opposing interests and parties. (Figure 5)

The goal of this digital project is to walk visitors through the complex and complicated political, social, and cultural terrain of the spatial narrative of Lincoln, Nebraska as a representative of the Gilded Age Great Plains city. By exploring in detail the early events of one Plains city, the project hopes to provide an understanding of similar dynamics and development occurring in other cities across the region at the time.

Lincoln: A Case Study of the Gilded Age Plains City

Gilded Age Lincoln was an island of activity and light amid the vast darkness and solitude of the Plains landscape between Omaha, Nebraska and Denver, Colorado. Founded in 1867, the town existed as a frontier village in the 1870s with its impermanent clapboarded appearance, but by the end of the 1880s, the city had matured into a "real" town solidly grounded in brick and stone.

In 1889, Lincoln boosters maintained and emphasized that Lincoln was poised to become the next major metropolis on the eastern Great Plains. Their city was special, and comparative to no other; these claims, although some-what founded, were superficial. Urbanization was transforming all of the western states at the time, not just the Great Plains, and Lincoln was no different from a wide range of cities also experiencing an extended boom of growth. All across the United States, places like Omaha, Minneapolis, Wichita, Topeka, Sioux Falls, Cheyenne, Denver, San Francisco, Portland, Los Angeles, and even San Diego were on the rise. Keep in mind as you explore the Gilded Age City digital project that the formula for growth and development in Lincoln was remarkably similar to those running these cities; only the degrees of change vary. As in some cases, even the same people were involved with events from one place to the next, an occurrence made possible by the most common link between places in the Gilded Age, the railroad.

Great Plains Urbanization: Marriage to the Railroads

When an earlier settlement of the Great Plains acquired a railroad, economic development dramatically increased. The more direct the connection a town or city had to the transcontinental railroads corridors of the time, the more vigorous were the economic currents running through it. The transcontinental railroad lines of the Kansas Pacific, Union Pacific, Chicago, Burlington and Quincy, the Great Northern, and Northern Pacific made cities, such as Omaha, Kansas City, Missouri, and Kansas City, Kansas important exchange points. The cities became regional entrepots or "gateway cities" and thus, wedded to the particular railroad system within the national economy.

Apparently in the 1880s, secondary places like Lincoln and Topeka, Kansas sought to dislodge the advantages that larger cities had attained to achieve their metropolitan status. They did so by connecting themselves to regional railroad systems, such as the Rock Island & Pacific Railroad, which did not produce the same economic injection into cities as the larger transcontinental railroads. Although many of these secondary places remained just a stop on the rail lines versus growing into a metropolis gateway or transportation hub, the depot and railroad yards became the central point of urban growth.

By 1889, Lincoln had become a regional hub for the Burlington and Missouri River Railroad, as well as the Rock Island & Pacific Railroad, Midland Pacific Railroad, Omaha & Southwestern Railroad, and the Nebraska Railway.

Lincoln's Early Development

As in all developing cities, the layout, or spatial arrangement, of Lincoln became differentiated. Special districts evolved, each with connected activities and specific economic functions, numerous examples of which are explored in detail throughout the site. Clicking on the maps shows that Lincoln had its central business district of downtown, its railroad yards and nearby manufacturing district, its smaller warehouse wholesaling district, and its specialized areas for the University of Nebraska and State Capitol, all of which were increasingly circled by residential neighborhoods differentiated by wealth, size of houses, and, ultimately, social class. (See Spatial Narratives in Time and Place).

Within these differentiations of society came an increasing variety of social, political, and cultural views on how to develop and run Lincoln. Even in a city of only 25,000 in 1890, a common sense of purpose and community seemed to be eroding as different occupational groups, social classes, and constituencies evolved their own self-interests in regards to urban development.

The purpose of this website is to open up these various districts to examine interactions and overlap of city residents within each sphere. Through the narrative of Professor Timothy R. Mahoney's examination of the murder of John Sheedy and the resulting trial, the inner political and social dynamics of young, developing Lincoln come to life once again. Spatial narrative of city residents from all walks of life and gender provide a guided tour of Gilded Age Lincoln, and invite visitors to travel at will through the neighborhoods and embedded histories of each.

People:

Sheedy, John [Narrative]

[Brief Biography]

Additional Information about the Interactive Map

Panoramic maps were a popular art of the Gilded Age that produced views of cities all over the Midwest and west from the imagined perspective of a bird in flight, thus earning the title "birds-eye view." Much like aerial photography of the 20th century, historians see this format as a means for people to encompass complexity in another time period by utilizing a unifying view point of a space. The Lincoln panoramic was produced by the Henry Wellge & Company. Henry Wellge (1850–1917) produced panoramic art in twenty-four states issued under Henry Wellge & Co., Norris, Wellge & Co., and the American Publishing Co.

Information about highlighted buildings was encoded for use with the interactive Abode Flash map according to the Text Encoding Initiative. The data was derived from the following sources: Cherrier's Lincoln City Directory, The Cherrier Directory and Publishing Co., 1890; Hoye's Directory of Lincoln City for 1891, Hoye Directory Company, 1891; and Hoye's City Directory of Lincoln For 1892, State Journal Printing Company, Lincoln, Nebraska, 1892. When discrepancies occured between these sources, unless other evidence was available, information from the 1891 directory was used.